Module 4: Laminitis

Laminitis is a painful and potentially devastating condition. Prevention is certainly better than cure and although diet is not the only risk factor, it is one we can influence – unlike genetics! Brushing up on your knowledge of the latest feed and management advice will help you to advise your customers how to reduce their horse’ s risk. Being able to spot the signs of an attack early will help to maximise the horse’s chance of recovery if they do develop laminitis.

This training section is full of tips and information but for specific advice, please advise your customer to contact the Care-Line, especially if the customer’s horse/ pony is severely insulin dysregulated.

What is laminitis?

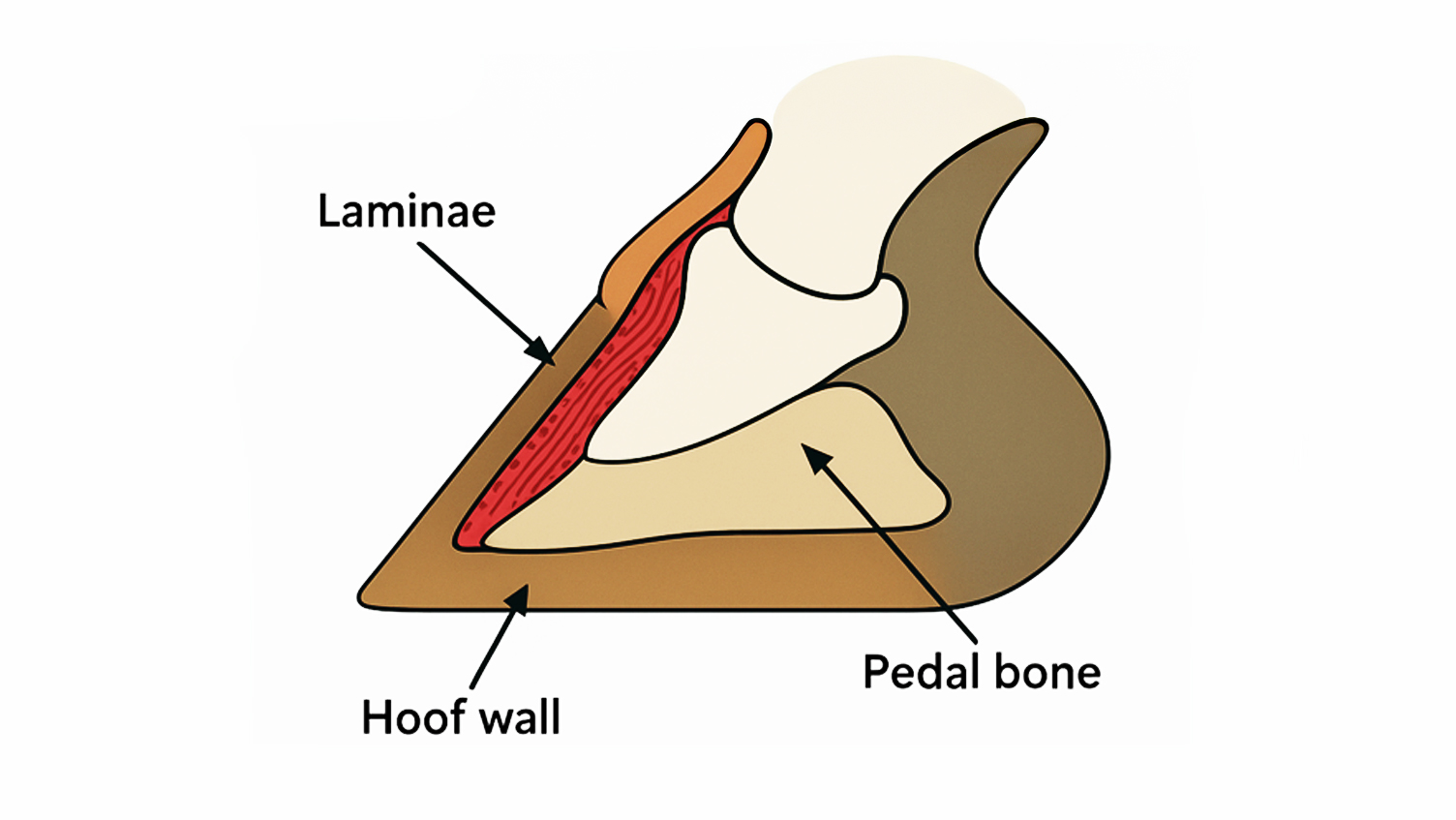

Laminitis can be described simply as damage or disruption to the laminae, causing varying degrees of pain and lameness. The laminae are the tissues which attach the pedal bone to the hoof wall.

What causes laminitis?

In general, most cases of laminitis are now considered to fall into one of the following categories:

Hyperinsulinemia associated laminitis (HAL).

Laminitis related to inflammation or toxemia e.g., as the result of a retained placenta or a severe infection such as pneumonia

Mechanical laminitis or ‘supporting limb laminitis’ as a result of excess weight bearing due to an infection or injury in the other leg.

HAL is now considered the most common form of laminitis and includes cases of laminitis associated with Pituitary Pars Intermedia Dysfunction (PPID) or Equine Metabolic Syndrome (EMS).

The exact sequence of events or ‘mechanism’ that leads to the development of laminitis remains elusive. HAL may be triggered by the horse/ pony eating enough non-structural carbohydrate (NSC) or ‘starch and sugar’ from feed or forage to cause a sufficiently high or persistent increase in the amount of insulin circulating in the blood, although exactly how this causes laminitis is still not clear.

Which horses & ponies are at the highest risk?

Laminitis is thought to affect up 1 in 10 of the equine population. Although any horse or pony can develop laminitis, a number of risk factors have been identified including:

- High intakes of non-structural carbohydrate (NSC) or ‘starch and sugar’.

- Insulin dysregulation (ID).

- Genetics e.g., certain native breeds.

- Pituitary Pars Intermedia Dysfunction (PPID) or ‘Cushing’s syndrome’, especially in the presence of ID.

- A history of laminitis.

- A recent change in grazing or move to ‘high quality grazing’ - regardless of the season!

- Recent weight gain and obesity, particularly in horses and ponies with a body condition score (BCS) of 7 or above on the 1-9 scale (although lean horses and ponies can be at risk too).

- A low concentration of adiponectin in the blood. Adiponectin is a hormone produced by fat cells thought to help improve insulin sensitivity.

Insulin dysregulation

We’ve known that insulin dysregulation increases the risk of laminitis for some time, but recent research published in collaboration with SPILLERS* was the first to quantify the level of risk. By measuring the concentration of insulin in the blood, researchers were able to categorize previously non-laminitic ponies as being at low, medium or high risk. Over a 4year period, the chance of laminitis was predicted to be approximately:

6% in the low-risk group

22% in the medium-risk group

69% in the high-risk group

* Knowles, EJ, Elliott, J, Harris, PA, Chang, Y-M, Menzies-Gow, NJ. Predictors of laminitis development in a cohort of non laminitic ponies. Equine Vet J. 2022; 00: 1– 12. https://doi. org/10.1111/evj.13572

What about EMS?

The term Equine Metabolic Syndrome or ‘EMS’ was first used in the early 2000’s and has been the subject of some controversy. The definition has evolved over the last 15 years and one of the most important changes is the recent acknowledgment that not all horses and ponies with EMS are overweight or have regional fat pads.

EMS is now described as a collection of risk factors for HAL. Insulin dysregulation is the single consistent feature meaning horses/ ponies must be ID to be diagnosed with EMS. Other risk factors include obesity and/ or regional fat pads, weight loss resistance and other metabolic alterations including an imbalance of certain fats in the blood and alterations in certain hormones/ proteins produced by fat cells, including adiponectin. The combination and severity of risk factors present varies between individuals.

Can you spot the signs?

Being able to spot the signs of an episode early maximises a horse’s chance of recovery, so it pays to be vigilant, especially as subtle signs such as a slight reluctance to turn or shortening of stride can be easily missed. Signs of laminitis can include:

- Weight shifting.

- Changes in gait including a shorter stride or ‘pottery’ movement.

- Reluctance to turn or cross the hindlimbs.

- Reluctance to walk on hard, stoney or uneven ground.

- Lameness.

- Abnormal stance.

- A strong/ pounding digital pulse.

- Hot feet.

- Signs of pain such as sweating and increased pulse, temperature and respiration rates (which may be mistaken for signs of colic).

- Refusal to move or stand in severe cases.

Starch & sugar

Providing a diet low in non-structural carbohydrates (NSC) or ‘starch and sugar’ is one of the top priorities for managing those at risk of laminitis. However, the different terms used to describe starch and sugar can sometimes cause confusion. Here’s a quick guide to busting the jargon:

Non-structural carbohydrate (NSC) = starch + water soluble carbohydrate.

Water soluble carbohydrate (WSC) consists mainly of simple sugars, such as sucrose, and fructan.

Fructan is the ‘storage’ form of sugar in the majority of UK grasses and consequently hay and haylage.

How much starch & sugar is ‘too much’?

Percentages are a useful starting point when it comes to comparing one feed against another, but they only tell part of the story. Ultimately, the amount of starch and sugar a horse will consume from any feed depends on how much of it they eat.

For example:

- 2kg of feed with a combined starch and sugar content of 9% contains 180g of starch and sugar.

- 1kg of feed with a combined starch and sugar content of 18% also contains 180g of starch and sugar.

When it comes to choosing ‘bucket feed’ (as opposed to forage), consider the feeding rate and the amount of starch and sugar the horse will consume, rather than basing the choice on percentages alone. Restricting NSC intake to less than 0.5g per kilogram bodyweight per meal (<250g per meal for a 500kg horse) should be a suitable guide for most horses provided they are not severely insulin dysregulated.

Bucket feed

- Balancers are ideal for good doers as they provide the vitamins, minerals and quality protein needed to balance forage while adding very limited amounts of energy (calories), starch and sugar to the diet.

- Choose fibre-based feeds that are low in starch and sugar for those unable to maintain a healthy weight/ body condition on forage and a balancer.

- Choose feeds that are high in oil (as well as low in starch and sugar) for poor doers – gram for gram, oil is approximately 2.5 times higher in energy compared to cereal grains but starch and sugar free.

- If weight gain is required, oil can generally be added on top of the horse’s current feed at a rate of up to 100mls per 100kg bodyweight per day i.e., 500mls per day for a 500kg horse. However, high oil diets should be balanced with additional vitamin E so it’s wise to contact a nutrition specialist before adding oil to a horse’s feed. Any oil fed should be fresh and introduced gradually.

- Divide feeds into multiple small meals. This helps to reduce the amount of starch and sugar consumed in each meal and may be of increased importance for severely insulin dysregulated horses and ponies – speak to one of our nutrition specialists for more advice.

How much forage should be fed?

Ideally horses and ponies should be provided with as much suitable forage (or if necessary, a forage replacer) as they will eat, while being mindful of excess waste. If your customer is concerned about weight gain, suggest they try to find ways of reducing the calorie density of their forage e.g., feeding soaked hay or gradually replacing part of the forage ration with clean straw, rather than restricting the amount of forage fed where possible. However, free access to forage may not be appropriate for good doers in which case, some level of restriction will be needed.

For most overweight horses and ponies, total forage intake should not be restricted to less than 1.5% of current bodyweight on a dry matter basis. For a 500kg horse without grazing, this is equivalent to approximately 9kg of hay if it is to be fed dry or 11kg if it will be soaked before feeding on an ‘as fed’ basis (the amount of hay that needs to be weighed out). The difference in feeding rates often causes confusion, for specific advice, call the Care-Line.

Grazing

Did you know that a 250kg pony turned out to pasture 24/7 may consume enough energy (calories) to fuel a 500kg racehorse and almost 2kg of simple sugars from grass alone every day?!

Tips for managing grass intake:

- Restrict or remove grazing – horses and ponies at very high risk may need to be removed from grazing completely, especially at certain times of year such as during spring and autumn.

- Beware of binge eating! Turning out for short periods may be counterproductive. Ponies can consume almost 1% of their bodyweight (dry matter) in only 3 hours. This may equate to two-thirds of the total daily forage allowance for those on a weight loss diet!

- Consider using a grazing muzzle. Grazing muzzles have been shown to reduce grass intake by approximately 80% in ponies turned out for three hours, regardless of the season. However, some horses and ponies may simply eat more once their muzzle has been removed to compensate, so consider stabling or non-grass turn out for remainder of the day. Grazing muzzles should always be introduced gradually, be well fitted and should not be left on 24/7.

- If available, consider non-grass turnout for those at very high risk or at certain times of year. This can be a useful way of encouraging voluntary exercise and providing time for socialisation.

- Try turning out at times and in places where WSC levels may be lower, for example overnight, early in the morning and in shady areas or on cloudy days.

- Avoid turning out on pasture exposed to bright sunlight in conjunction with cold temperatures e.g., sunny frosty mornings.

- Avoid turning out on recently cut hay stubble.

- Where possible, avoid pastures with grasses likely to a have high WSC level content e.g., predominantly rye grass pastures.

Soaking hay to reduce the sugar content

Soaking hay helps to reduce the WSC or ‘sugar’ content, but losses are highly variable which means there is no guarantee that soaking will ensure suitability for laminitics. Ideally have hay analysed (for WSC using the wet chemistry method) and use soaking as a back-up. For more advice on forage analysis contact the Care-Line.

- As a guide, soak for 1-3 hours in warm weather (ambient temperature 16°C and above) and 6-12 hours in cold weather.

- Make sure the hay is fully submerged in the water.

- Use fresh water for every soak.

- Due to the loss of nutrients (and therefore dry matter) into the water, each slice of hay will contain more water and less ‘hay’ post soaking. As a practical guide, increase the amount of hay soaked by 20% to compensate.

- Steaming has little effect on WSC levels. Although not a practical solution for all owners, soaking followed by steaming (in a commercial steamer) helps to achieve the best of both worlds if your customer is trying to reduce the level of ‘sugar’ in the hay and improve hygienic quality.

Feeding straw

- Consider replacing 30-50% of the total forage ration with straw for good doers without dental issues.

- Any straw fed should be of good hygienic quality and introduced gradually

Monitoring weight & body condition score (BCS)

- Aim to monitor a horse’s bodyweight weekly and BCS fortnightly.

- A BCS of 5 out of 9 is generally considered ideal although allowing good doers to enter the spring at a leaner score of 4.5 may help to prevent excess weight gain.

- Some horses and ponies may have a large crest and/ or other regional fat pads despite being thin overall. In these situations, body condition scoring systems should be used with care – speak to one of our nutrition specialists for more advice.

- If a horse/ pony is overweight consider monitoring bellygirth weekly

Your customer thinks their horse / pony has laminitis; what should they do?

If your customer suspects their horse or pony has laminitis, suggest they stable them on a deep bed that goes all the way to the door and call the vet immediately. Box rest is essential for preventing further damage to the laminae and the vet will often prescribe pain relief. Initial diagnosis is often made based on clinical signs but in some cases X-rays, blood tests or other clinical tests may be needed to provide more information about the severity or potential cause of laminitis.

Congratulations

You have now completed Module 4: Laminitis and should have a basic understanding of the key risk factors, early warning signs, and how to guide customers towards suitable feeds and feeding practices for horses and ponies prone to or recovering from laminitis.

To secure your AMTRA points, don’t forget to take the short quiz now. This will test your knowledge, reinforce your learning, and ensure your completion is officially recorded.

You can now move on to the next topic in Module 4: PPID